We will gather that it was a Dry Flood, and that the term refers to the extinction of - apparently - all but a very few members of the human species by a nameless epidemic.

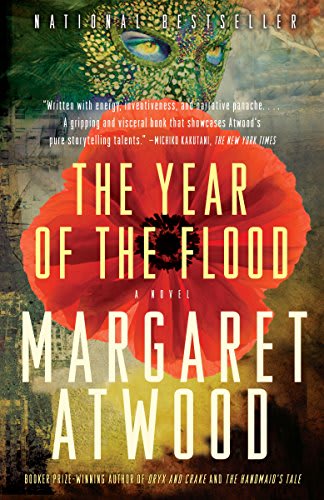

So, then, the novel begins in Year 25, the Year of the Flood, without explanation of what era it is the 25th year of, and for a while without explanation of the word "Flood". As it is, I must restrict myself to the vocabulary and expectations suitable to a realistic novel, even if forced by those limitations into a less favourable stance. I could talk about her new book more freely, more truly, if I could talk about it as what it is, using the lively vocabulary of modern science-fiction criticism, giving it the praise it deserves as a work of unusual cautionary imagination and satirical invention. Who can blame her? I feel obliged to respect her wish, although it forces me, too, into a false position. She doesn't want the literary bigots to shove her into the literary ghetto. This arbitrarily restrictive definition seems designed to protect her novels from being relegated to a genre still shunned by hidebound readers, reviewers and prize-awarders. In her recent, brilliant essay collection, Moving Targets, she says that everything that happens in her novels is possible and may even have already happened, so they can't be science fiction, which is "fiction in which things happen that are not possible today". But Margaret Atwood doesn't want any of her books to be called science fiction. T o my mind, The Handmaid's Tale, Oryx and Crake and now The Year of the Flood all exemplify one of the things science fiction does, which is to extrapolate imaginatively from current trends and events to a near-future that's half prediction, half satire.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)